We've been thinking about Substack all wrong

The company that promised a new paradigm looks a whole lot like the old one

⏱ This is a 6-minute read.

The question is trite by now in newsletter circles, but it is still the one I get most often: "Should I launch on Substack?" Frankly, I count it as a win when it's phrased as a question. It suggests my interlocutor is at least aware of other options. It's more often a statement – "I'm launching a Substack" – which inevitably prompts me to deliver an unsolicited product review and lose all my media friends. From now on, I'll just send them this article.

The promise of Substack is that writers can live from their craft and free themselves of controlling old editorial institutions thanks to a platform that lets them build a direct and lucrative relationship with their audience and – crucially – keeps them in complete control of their publication. In Silicon Valley parlance, Substack is "building a new economic engine for culture." That's the pitch I got when, in 2019, I met cofounder Hamish McKenzie, a former journalist in whom I recognised the same drive I had to create new paths for the industry and who convinced me to sign up. I secured isa.substack.com and didn't do much with it at first, until I started my podcast Borderline and its attendant newsletter in spring 2020. By spring 2021, I was one of the first wave of early adopters who left Substack when a succession of product decisions belied the control and independence we were promised.

Whose brand is it anyway?

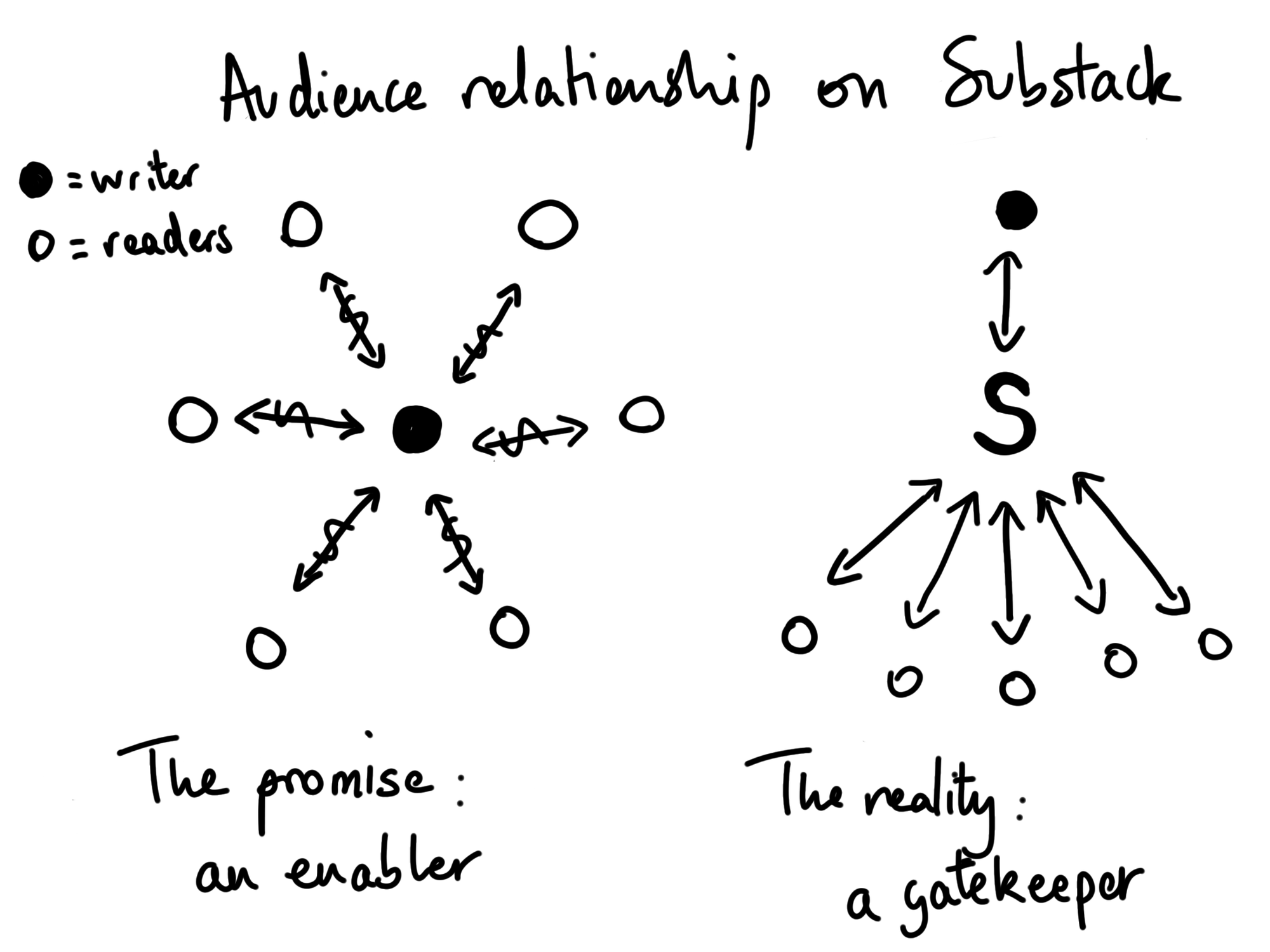

The trigger for me was when the company started encouraging readers to access my content within substack.com while unsubscribing from my emails. Suddenly, I was one of many on a Web platform that foregrounded its own brand, instead of having as unmediated a relationship as possible with my audience via their email inbox. My own brand was becoming invisible, a 20x20 pixel logo on a same-y website with hundreds of other creators, where catching my readers' attention was down to Substack's product decisions, never my own. Every one of those product decisions since has confirmed my hunch, from launching an app that heavily incentivises reading there over the inbox, to promoting a follow function – a non-exportable audience list – over email subscriptions, and creating an algorithmic feed.

As I told The Observer at the time, I wanted newsletter software that "could recede in the background and allow my own brand to shine." I could see the signs of Substack becoming something quite different. It was subtle, it was couched in better UX speak and the illusion of choice, but it was a land grab. My readers were becoming Substack's users, and I was becoming a provider of content to the company I had hired to be my provider of software.

Meanwhile, Substack's star was rising in pop culture. Phrases like "Substack writer" started creeping up. Publications were secondary to that conversation, and when a few handpicked star creators were cited, it was to feed Substack's own hype ("look who joined this week!"). All writers became lumped together in a collective they had never asked to be a part of (in a way that never happened to all users of, say, Google Docs) with assorted unsavoury characters Substack refused to distance itself – or the rest of us – from in the name of unfettered free speech. But I'm not even going to get into that. Before it's a moral issue, my objection to building on Substack was purely a business decision.

When I – or Anil Dash, or Lex Roman – say "don't call it a Substack," we're objecting to the genericisation of newsletters under a corporate name that hogs the credit for thousands of individual entrepreneurs' own hard work and invisibilises the media brands they are trying to build. We may well have lost that battle already – I regularly have to correct people who call "a Substack" newsletters that don't even operate there – but we can at least call it out.

Network effects or Ponzi scheme?

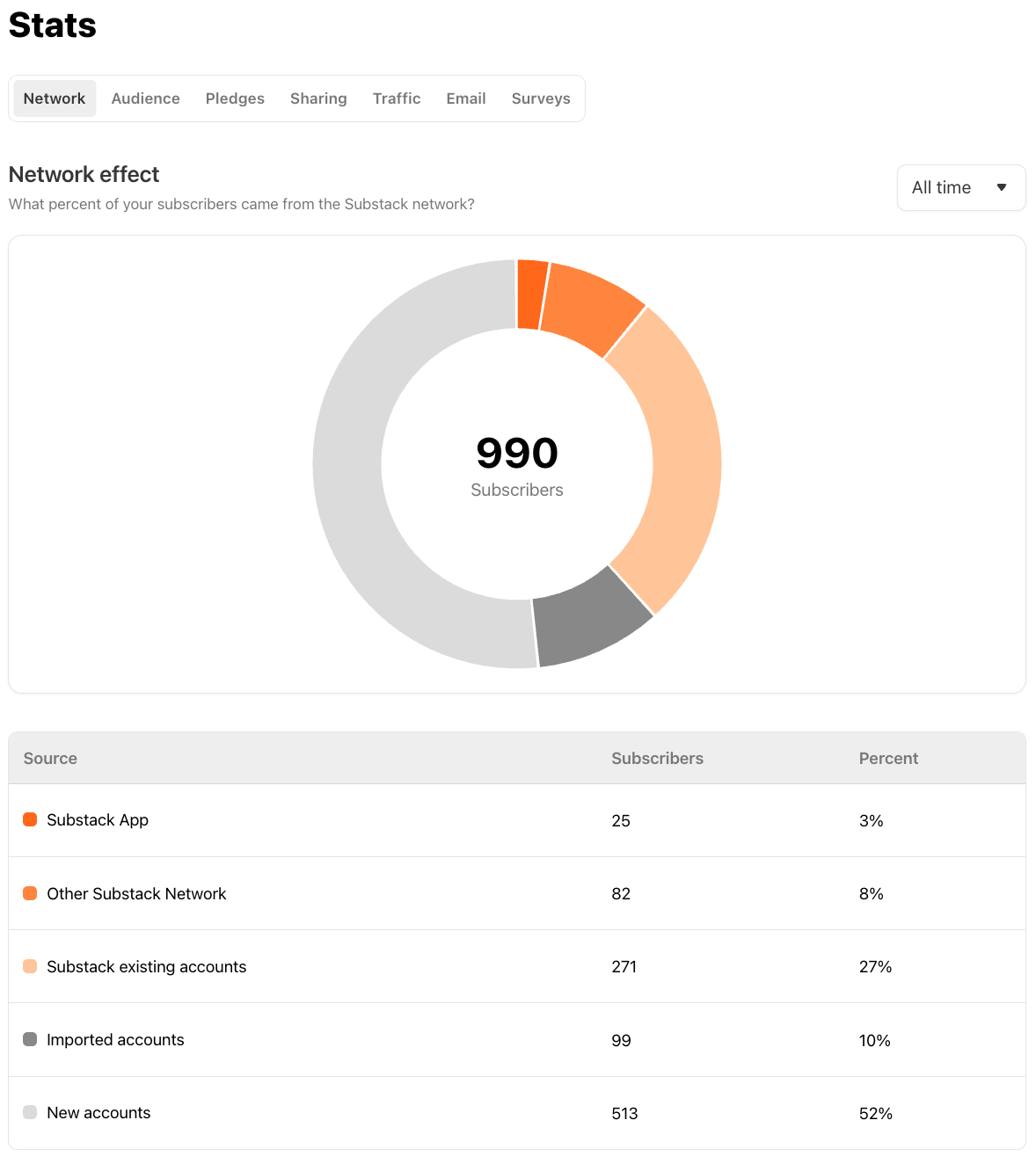

And yet, even I have been tempted to go back to Substack. It is always down to growth envy. Substack boasts impressive network effects, claiming that "more than 40% of all new free subscriptions and around 20% of paid subscriptions to Substacks come from within (their) network." If that is true, that is a massive advantage over competitors, so it's a claim worth digging into.

In summer 2022, new signups to my Substack publication – now more than a year inactive and with a large "we've moved!" post at the top – suddenly ticked up. I got curious. It turns out Substack had launched a recommendation feature and my friend Jonn Elledge, writer extraordinaire of The Newsletter of (Not Quite) Everything, had listed me as a fellow traveler. Anyone who signed up for his publication was encouraged to sign up for mine and a few others, and – clever, if not entirely honest – Substack ticked all boxes by default. When Jonn had a good day, I had a fractionally good day.

Who should get the credit for these new free subscribers? I'd say Jonn, his fantastic writing and our years of friendship and mutual professional respect. The blogroll is as old as blogging, and recommendations or cross-publishing with similar writers is newsletter growth 101. This would happen with any CMS, though I'll grant Substack that within the same platform, you can make it happen in one or two fewer clicks. That's enough for Substack to dub it a Network Effect™️.

When I understood what was happening, I thanked Jonn for his support and asked him to kindly direct readers to my new online home instead. Impossible – Substack only lets publishers recommend other Substack publications. It doesn't want to take audiences to the wider Web. That's a classic walled garden play, which should get your Spidey senses tingling if you've ever had dealings with a tech company. For a while, I set up an automation that signed up these new arrivals to my Ghost-powered website instead (affiliate link, see disclaimer below). I quickly turned it off. What's the value of a reader who hasn't even noticed that they're signing up for a defunct publication? Did they mean to read me or did they get tricked into not unticking a box? The Network Effect™️ can net you a lot of junk.

More recently, I have referred 30 new subscribers to Jim Waterson's London Centric when I called out his launch to my large LinkedIn following and again when I shared his reporting on our local park in my neighbourhood Facebook group. Since I copied the referral link while logged into my Substack account, this too counts as a Network Effect™️. Everywhere else, it would be a LinkedIn or Facebook referral.

These are just two examples of Substack's more than cavalier approach to subscriber attribution. Writers who check their stats dashboard, which conveniently opens on the Network Effect™️ tab, must think they'd be nothing without Substack. That's the point. The company takes credit for all referrals with the remotest connection to its app or website, even when it did none of the promotion work. Cheekiest of all is the "Substack existing accounts" category, which the company defines as "Readers who could more easily subscribe to your publication because they already had a Substack account." Seriously. They take credit when people don't have to type out their full email address. Supreme irony: They'll take credit for most clicks from this article.

Writers recommend other writers they like. Readers share what they read with their friends. That's not a Network Effect™️, that's just the way the Internet works. Substack gets new writers to sign up by letting older writers spread the fiction that they owe their growth entirely to Substack. I believe we call that a Ponzi scheme.

Oooooh... it's just another social network

What are we left with then? A walled garden strategy, a claim to network effects real or imagined, a follow ecosystem, an algorithmic feed, unreliable metrics, the artificial inflation of engagement on new products, the invisibilisation of publisher brands, the capture of the audience relationship, blitzscale growth to satisfy venture capital investors, big promises to early adopters followed by progressive enshittification, controversial moderation decisions... oh wait, it's like every social network ever built.

Substack pretends to be the CMS that powers the new independent media era, when it's really a platform of the old scale era. The second you look at Substack as social media, it starts to look a whole lot better. I'm even ready to argue that as social platforms go, Substack is one of the better ones for creators in a field that is notoriously exploitative. It's easy to use out of the box (sort of). It enables fast growth (that's at least half real). It provides transparent(ish) monetisation. It lets you (mostly) own your audience list. It doesn't cost you a thing until you earn something (then it takes quite a bit of it). That's why I see little harm in larger publishers such as New York Magazine trying out Substack as part of a broader social portfolio or creators using it as a process blog, without intending to make it their main income.

But as a serious CMS and the single engine of a small business, Substack has big limitations. Crucially, the service quickly becomes far more expensive than its competitors as you grow. It prioritises its brand over yours and offers no brand safety. It is a black box that you cannot customise or control and that will not grow with your business. It only enables a one-legged business model – subscriptions –and doesn't allow for proper audience knowledge or targeting. The product direction is completely out of your hands. You are always one outside decision away from a business catastrophe. As The Food Section's Hannah Raskin wrote when she moved to her own custom tech stack, "Substack is a terrific platform for writing, but a lousy one for business."

That's because Substack is built on the premise that journalists don't want to think about business. Give them a turnkey platform and they'll ignore everything else. Somehow we buy the lie that we can build a successful business without ever thinking about how businesses succeed. In traditional newsrooms, we delegated that task to "the business side" and hid behind "church-and-state" walls and segregated lifts. Now, even in businesses of one, we've found a new way to externalise dealing with reality.

I do not begrudge the Substack team any of their decisions. They are running their business as they see fit for their and their investors' benefit. It is time we do the same. I raise the alarm when I see entire media businesses built on that single platform. I worry about an industry that refuses to accept it's not other businesses' job to make ours succeed. Again and again, we place ourselves in the palm of other people's hands and we cry foul when they clench their fist. When will we learn?

A framework for choosing better

I can't leave you without a solution. I could tell you I use Ghost and I love it. But the point is not to replace blind allegiance to one tool with blind allegiance to another. Absolute self-reliance is a mirage, but there are bargains I feel more comfortable signing than others. Here are some of the things I think about when choosing my suppliers, with more details at the link below.

- Software over platforms: Tools should recede in the background. My readers have no reason to know the brands of my tech stack.

- Flat rates: Revenue cuts are almost always significantly more expensive. If you believe in what you're building and have even a little bit of capital, pay upfront.

- Openness: Call me an old Web utopian but I am sick of walled gardens, data that doesn't port and building on rented land. I have to own what I make. This is non-negotiable.

- Customisability: You don't know where your business will go. The best tools are easy to start with but infinitely customisable when you grow.

- Values: I like to feel good about whom I give my money too and understand their incentives. Accessible teams, open product roadmaps, revenue models, VC-backed vs bootstrapped... those things will matter a lot more than you first realise.

Hey, you read to the end!

Don’t miss future articles like this one; let me into your inbox.