Mass migration is inevitable. The global North should welcome it.

Climate change and demographics are setting the stage for a massive reshuffling of the human population, argues Parag Khanna.

Climate change is making or will make wide swaths of the planet uninhabitable, pushing people north. Economic inequality is driving people of the global South far from home in search of opportunity. And opportunities exist. Countries in the global North are ageing, depopulating even, losing their workforce and their tax base, pushing their women out of the workforce to care for the young and old, when the old are lucky enough not to die alone. It shouldn't be that hard to put two and two together and create migration policies that benefit all of humanity. So why won't we?

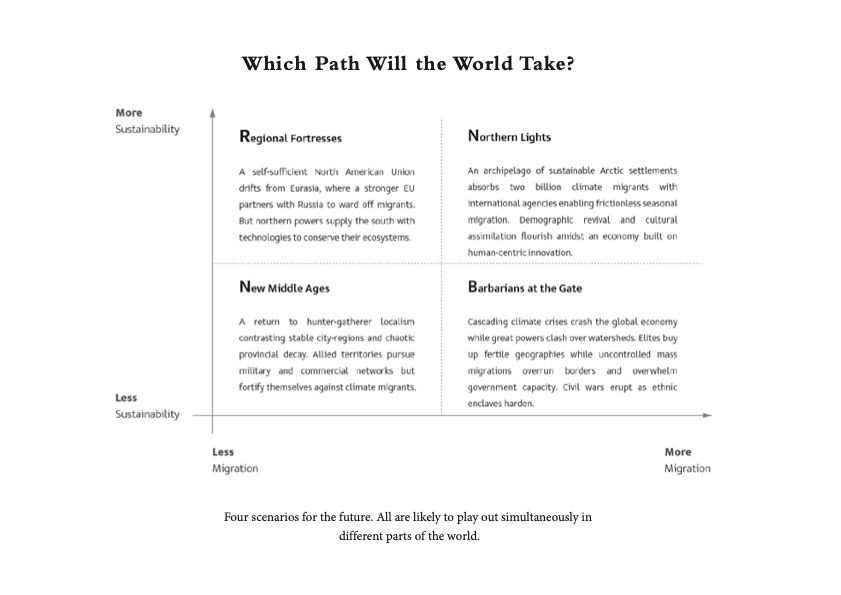

That's the picture Parag Khanna paints in his book Move, a global look at the future of mass migration. He envisages four scenarios for how humanity will respond to the inevitable movement of people. Suffice it to say, they're not all good – unless we make it so. "The human population will relocate," Khanna told me. "We might as well see it coming. We might as well plan for it. We might as well make the most of it and prepare and even generate what our next and more progressive and sustainable model of human civilisation is going to be."

Here are three ideas that jumped out to me. I recommend listening to the full conversation on the podcast or you can read the transcript here.

De-industrialised, depopulated regions will thrive on the new migration.

“People are moving in zigzagging ways all the time and in growing number. And it could mean going back to a place that you didn't think you'd go back to. Americans have been moving from North to South, from the Rust Belt to the Sun Belt because of the de-industrialization of the American Great Lakes region. But of course the Great Lakes region is America's climate oasis. It's the most propitious zone for human habitation, perhaps in the entire world, given the supply of fresh water. However, it doesn't have great economic circumstances right now. So I predict that all of those Americans who moved from the Rust Belt to the Sun Belt are going to wind up moving back to the Rust Belt because it's near the Great Lakes. And they'll be followed by many, many other Americans who live in drought stricken areas or areas where coastal flooding or other kinds of extreme weather phenomenon have affected those geographies.”

The countries that need migrants the most are the most hostile to them. This is generational short-sightedness.

“It's a status quo bias. It's a generational conservative bias. Older people who themselves are the ones most in need of caregivers, who mostly need to be imported, are the ones who are voting against immigration. They're not thinking about fiscal stability either because they're primarily concerned with the preservation of their entitlements in terms of the pension system, and so forth. But meanwhile, they're forgetting that if you're not importing young people, then you're not going to have a tax base in the future, but they don't care because they'll be dead. And unfortunately, because every position is so self-interested short term and over-simplified, you don't wind up getting the kind of pragmatic long-term, supply and demand-driven policy that you should have. As a voter, as a citizen, as a taxpayer, you should demand better. Everyone should have the common sense to take this complex issue seriously. And to, in a matter-of-fact way, calculate how many people your country needs and to make sure you're getting those people. Otherwise, at some point you cease to be a civilised country because your old people are dying alone. The women have to drop out of the workforce. None of this is necessary at all, right? But it's a self-inflicted wound and I personally wouldn't tolerate it.”

Cities have been and will be around much longer than states. And they want immigrants.

“Among the worst mistakes that a country can make is to go against the interests of its principal cities, right? There is no country, there is no economy without the city. And that's very true, even in a wealthy country, like the UK, where London is, you know, whatever, 30 plus percent of the GDP. That said, you don't want to see capital cities hoard resources and not distribute the wealth. That would also be problematic. But to make federal decisions that literally undermine yourself is a mistake. And of course, again, Brexit is a case in point in that. There is no great power in history that isn't built on great cities and the accomplishments of great cities and the connectivity and influence of great cities. Remember that we've had cities for 7,000 years. We've had modern nation states for a couple of hundred years and universally for only about 75 years. It is nothing more than a passing phase, right? And you can say that with complete confidence, despite all the maps on our wall telling you something different. Countries come and go. They're born and grow and collapse all the time. There are pipelines in the Middle East that predate Arab states such as we know them today. And after those states fall apart, the pipeline will still be there. There are cities like Damascus and Baghdad and Cairo and Beirut that have been around again for literally a couple of thousand years. Long before the modern state and long after those states are gone, those cities will be there. So make no mistake what the central unit of spatial organisation is for humankind. It is not the state. It is the city and it will always be the city.”

Listen to the full conversation on the podcast and see best excerpts below. You can read the transcript here.

Hey, you read to the end!

Don’t miss future articles like this one; let me into your inbox.