The post-Brexit immigration scheme ends in a month. Its flaws could show up in a decade.

Here are all the ways the EU Settlement Scheme could be a slow-motion crash. (It may well not be. We just won't know for a while.)

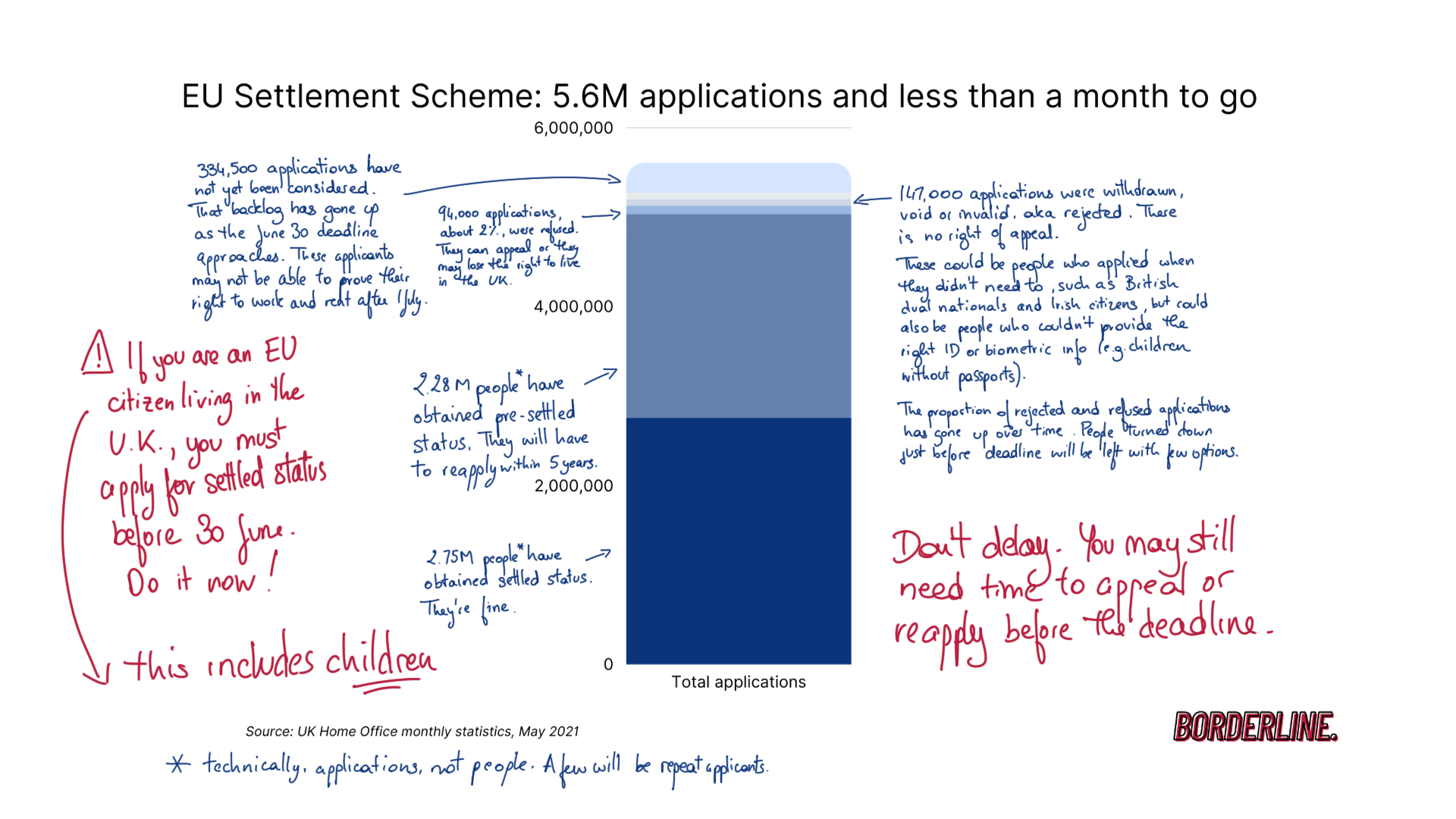

Update on 10 June 2021: The Home Office has released May numbers for EUSS application so here's an updated chart on the numbers.

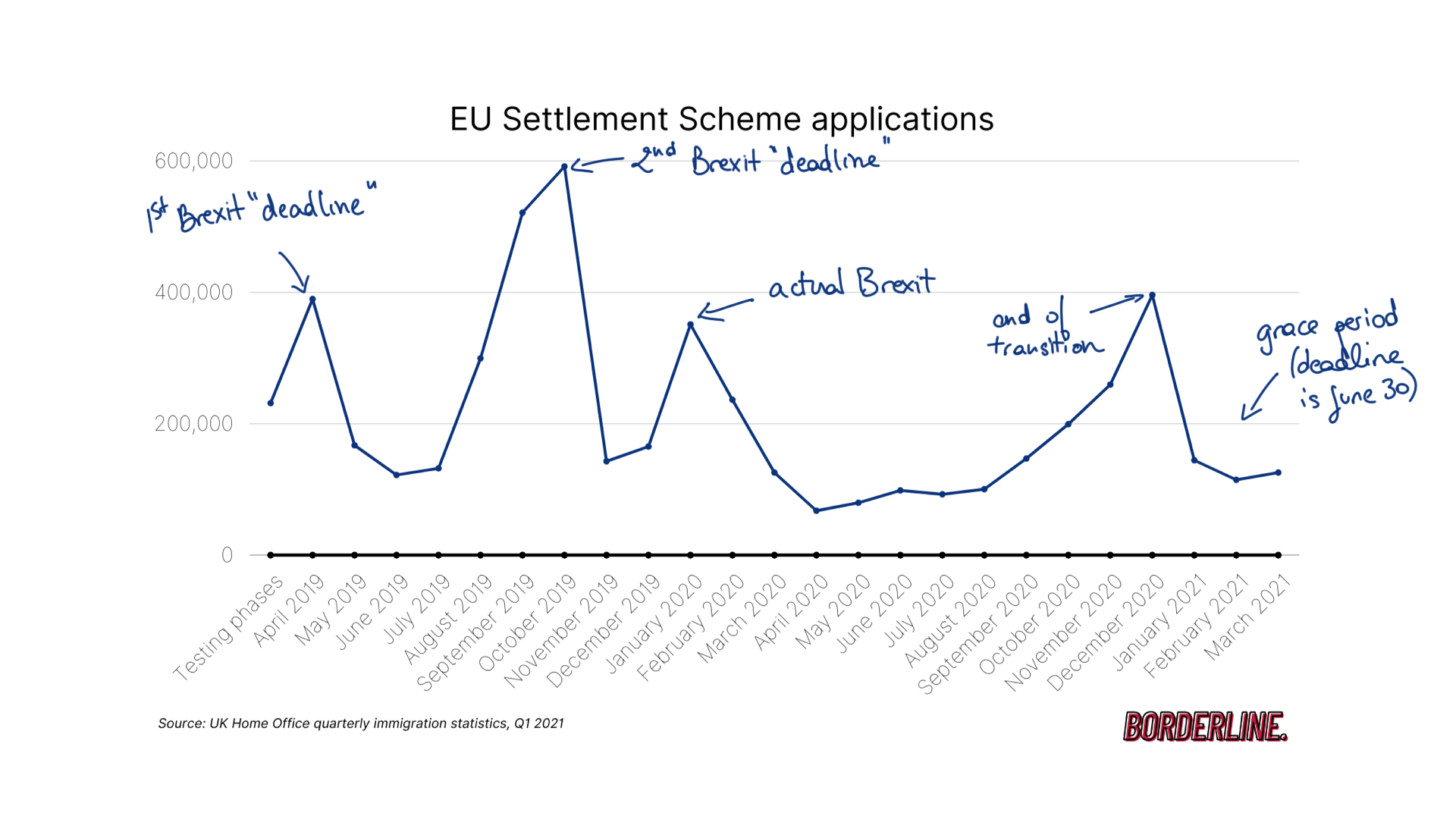

EU nationals* who moved to the UK before Brexit have less than a month left to secure their immigration rights. The deadline to apply to the Home Office's EU Settlement Scheme is 30 June, with limited recourse for snoozers. So how is that scheme going? On the face of it, rather well. In reality... we just don't know yet.

In one regard, the programme is a success: 5.42 million applications had been received by the end of April. (That's just about 5 million people; some had to apply twice.) In a normal year, the Home Office examines less than 100,000 settlement applications. To so quickly build a working administrative scheme of that scale is a feat. When it works, it works well: I applied back in February 2019 at the start of my lunch break and had the answer with dessert. All it took was my passport and an Android phone. By comparison, British citizens in France applying for a similar post-Brexit scheme still need to show up at the préfecture in person. (Your deadline is June 30, too; don't delay! Same in Malta, Latvia and Luxembourg.)

So if this thing had to exist – and we'll get to that – I'll concede it is pretty well executed so far. The problem with Britain's EU Settlement Scheme is that it could still fail years after it's ended. Here are five ways it could end up being a slow-motion crash.

1) We have no idea how many people we're missing.

Throughout the Brexit referendum period, there was a consensus: there were 3 million EU nationals in the UK. The advocacy organization fighting for EU citizens' rights in the UK is even called the3million. Looking at the latest EUSS application numbers, they might want to think about a name change.

The truth is the Office of National Statistics had never properly counted. An analysis by the Times showed that the presence of EU citizens in some parts of the country had been wildly underestimated. It was for instance thought that just 2,000 EU citizens lived in Arun, West Sussex; as of the end of March, 13,750 had applied to the settlement scheme there. The London borough of Hounslow is home to 50,000 more applicants (and counting) than initially estimated.

Not for the first time we learn the Brexit referendum debate lacked a basis in facts. The glass-half-full perspective says if the scheme has reached 160% of its target audience, surely everyone must be covered by now. The glass-half-empty says the government clearly has no idea how many people should be applying – and thus how many it's leaving on the side of the road.

Anyone who should apply and hasn't will be in the country unlawfully from July 1. The Home Office finally issued guidance laying out all the circumstances in which it will be lenient about late applications. Just not knowing about it will be an acceptable excuse for an undefined "initial period" unlikely to last beyond 2021.

2) People may not understand they're undocumented for years.

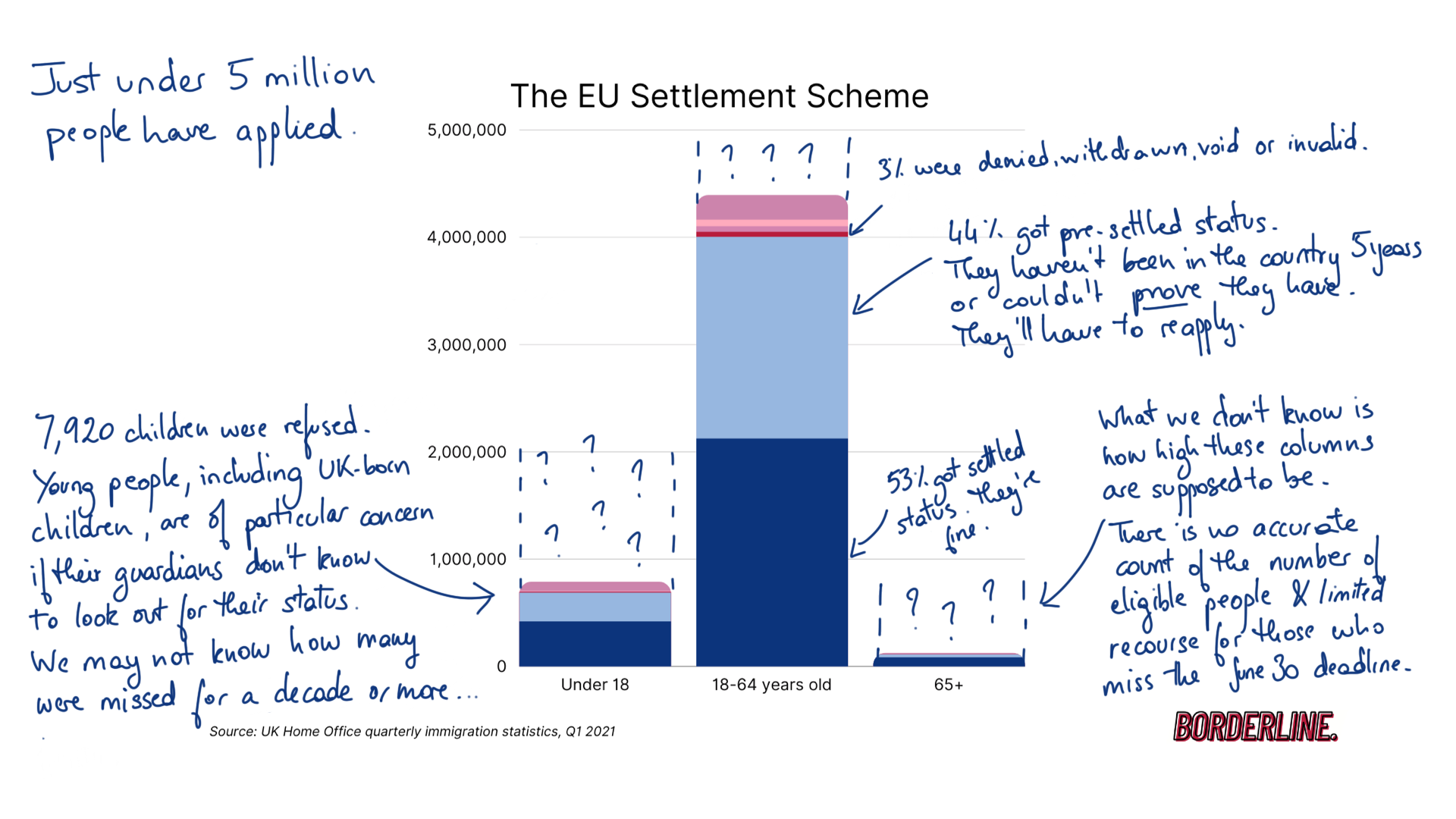

Children are of particular concern. If their guardians do not apply for them, it's in a decade or two, when they head to university, start working or rent their first home, that some may learn they are undocumented. They will have only known a British life. Some will have been born here. Will they know their rights? Will Home Office staffers know what to do in 2040? How many charter planes will fly to Romania or Poland before the public understands what's happening?

This could be another case of Dreamers, another Windrush in the making. Or it could very well not be. As an immigration reporter was telling me last week, the challenge with covering the EU Settlement Scheme is that you can only write about what might happen.

3) Pre-settled status is only a reprieve.

Two million people will have to apply again to make their status permanent in the next five years. Pre-settled status, granted to 44% of applicants, is easy enough to obtain. You only need to show you arrived in the UK before 31 December 2020 and you get 5-year limited leave to remain. Even a day of residence will do. Settled status, aka indefinite leave to remain, requires five continuous years of residence in the UK.

You can prove that in minutes if you're a typically salaried professional with pay-as-you-earn records. For financially independent or self-employed people, long retired pensioners, stay-at-home parents, people in care or anyone who hasn't had a tenancy or council tax bill in their own name, it's a different story. Meet the 96-year-old French woman who needs to track down ID 68 years after moving to London. Or the 27-year-old BBC journalist denied despite being here since age 10.

4) There's one final pandemic trap.

Continuous residency doesn't just mean having your main base in the UK. It means being physically in the country. Short absences are tolerated, but one must be present at least 180 days out of any rolling 12-month period or risk setting their residency clock back to zero. This requirement has been little advertised and I suspect will be some people's downfall. I only found out late in the game and built myself an Excel spreadsheet to keep track of my movements. (I've made one to share.) I realized after the fact I had almost disqualified myself from settled status in 2018, a particularly busy time in my career that saw me spend five cumulative months on foreign business trips.

Enter the pandemic. Many may have chosen to spend lockdowns back in their home countries. I know I did. Perhaps it felt safer. Perhaps they had people to take care of. Perhaps they got stuck mid-travel. Perhaps they lost a job in hospitality or retail and could no longer afford a London rent. If they were gone more than six months, they may no longer be eligible for settled status. (Here's how this works in detail.) The Home Office has not made a pandemic exception.

5) Lawful European residents are still open to discrimination.

Up until now, EU citizens could just flash their passport to assert their immigration rights. The settlement scheme, however, comes with no documentation. No visa, no residency card, no paperwork that other immigrants might get. Jus an email with no legal standing. The only way EU citizens can prove their status is to log onto the Home Office website, download a one-use code, give it to a potential employer or landlord, and trust them to log onto the Home Office website and verify themselves. EU citizen advocates fear many won't bother and will simply balk at employing or renting to Europeans. It will take the work of activists and journalists over years to determine whether that fear came true.

PS: We're also one cyber attack away from losing it all.

What now?

Mine is not to impute motives to the Home Office. For most people, the Settlement Scheme is straightforward and errs on the side of granting status. There should be fairly few people falling in the cracks. But even a 1% error rate among 5 million means 50,000 new undocumented migrants going through hell.

This could have been avoided if the British government had chosen a different method. Some EU countries, such as Italy, Spain or Portugal, have automatically granted rights to British citizens who lived there before Brexit. Others like Germany require they apply to a similar scheme, but with no consequences for missing the deadline.

It could have also been avoided if people's rights had not been stripped from them in a vote from which they were disenfranchised, only to be partially restored by administrative decisions subject to the interpretations of a single caseworker and the political mood of the day. But that ship has sailed.

*EU nationals is a shortcut, but actually the scheme applies to citizens of the EU minus Ireland (whose citizens are covered by the Ireland Act 1949), plus citizens of EEA countries Norway, Liechtenstein and Iceland, and of Switzerland.

Hey, you read to the end!

Don’t miss future articles like this one; let me into your inbox.