A photographer inside Nazi Germany's largest POW camp

Stalag VII-A was liberated 80 years ago today.

On April 29, 1945, Combat Command A of the U.S. 14th Armored Division drove into Stalag VII-A, near Moosburg, Bavaria, and freed more than 100,000 men. Brig. Gen. Charles H. Karlstad had learned of the prisoner of war camp's existence only earlier that morning when a delegation made up of a Red Cross staffer, a major in the SS and two detained British and American officers had driven up to meet him. The SS officer presented terms the Allied forces could not accept, which would have permitted the Germans' escape. Instead, US tanks advanced toward the camp, quickly undoing SS resistance but never using their artillery in order to preserve prisoners from friendly fire.

What they found, they could not have imagined. The overcrowded camp, the largest in Nazi Germany, housed 110,000 prisoners of war. Among them were 30,000 Americans including some of the renowned Tuskegee Airmen and men of the 100th Bomb Group, of Masters of the Air fame. Many men had been marched to Moosburg from other camps as US troops advanced. POWs were Brits, Frenchmen, Poles, Serbs, Moroccans, Australians... men from all allied nations and from all over Europe, enlisted men, officers, war correspondents, even reportedly a few women. Joy and relief overtook the tens of thousands of prisoners. One climbed up the roof to hoist an American flag. The scene is depicted fairly accurately in the last episode of Masters of the Air.

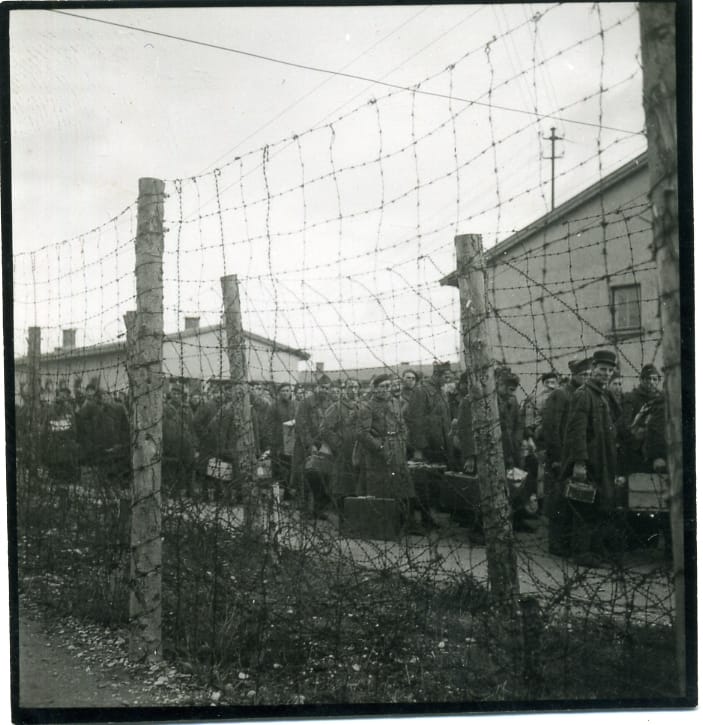

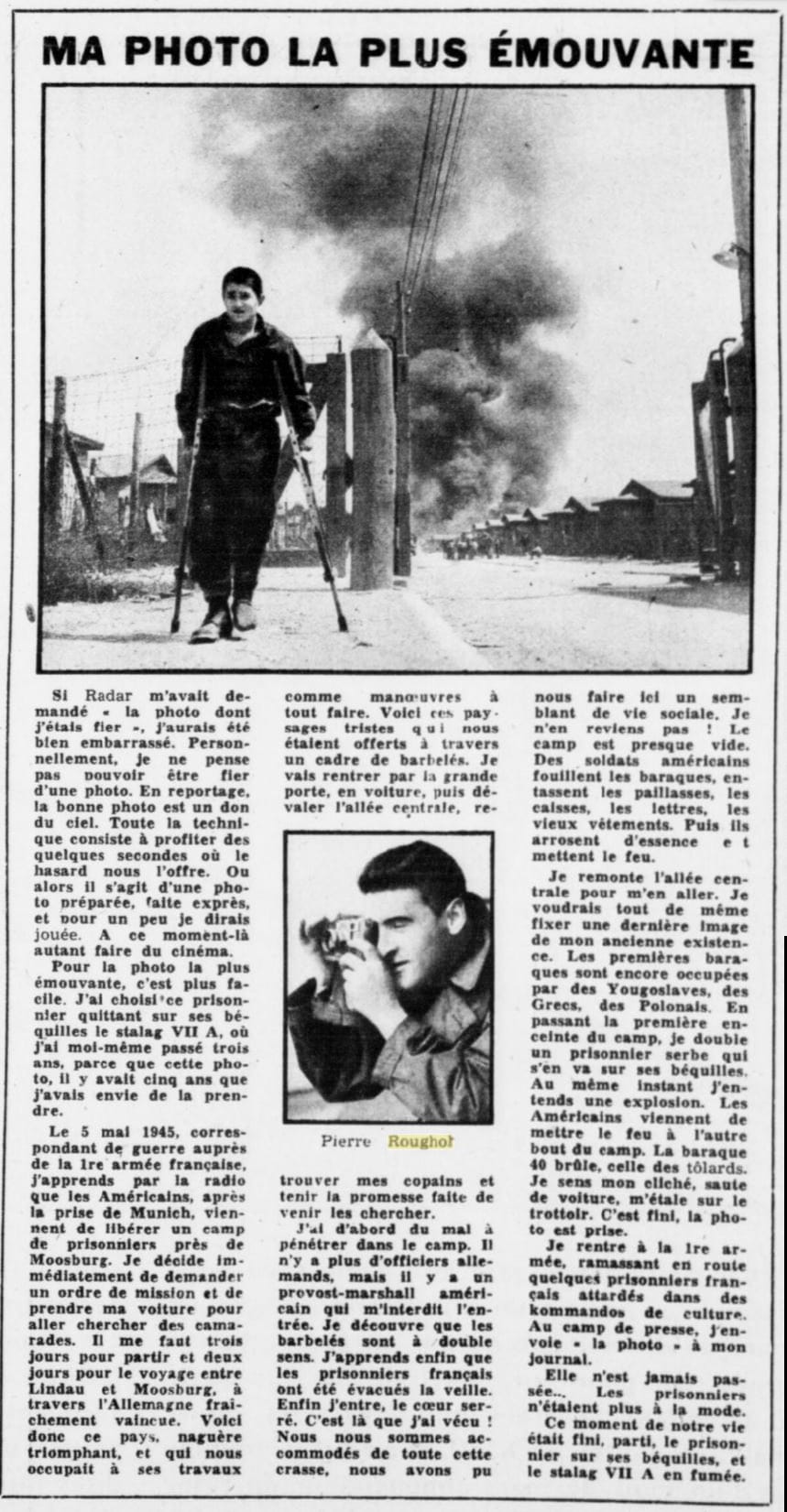

Circa 10 May 1945: Stalag VII-A, Moosburg, Bavaria, shortly after its liberation. Photo credit: Pierre Roughol archives. (No reuse without permission.)

Pierre Roughol was on the banks of Lake Konstanz, an embedded reporter with the First French Army, when he learned his old camp had been liberated. He and his brother, my grandfather Gilbert Roughol, had been prisoners there from June 1940, when they were separately taken prisoner with the whole of the French military, until November 1942, when they were miraculously released together. Gilbert was freed on medical grounds, having lost half his body weight in a camp where famine and dysentery were the norm. Pierre, at least according to paperwork, was able to accompany him as part of "la relève," the mostly failed Faustian deal that freed one French POW for every three young Frenchmen who submitted to mandatory work in German factories.

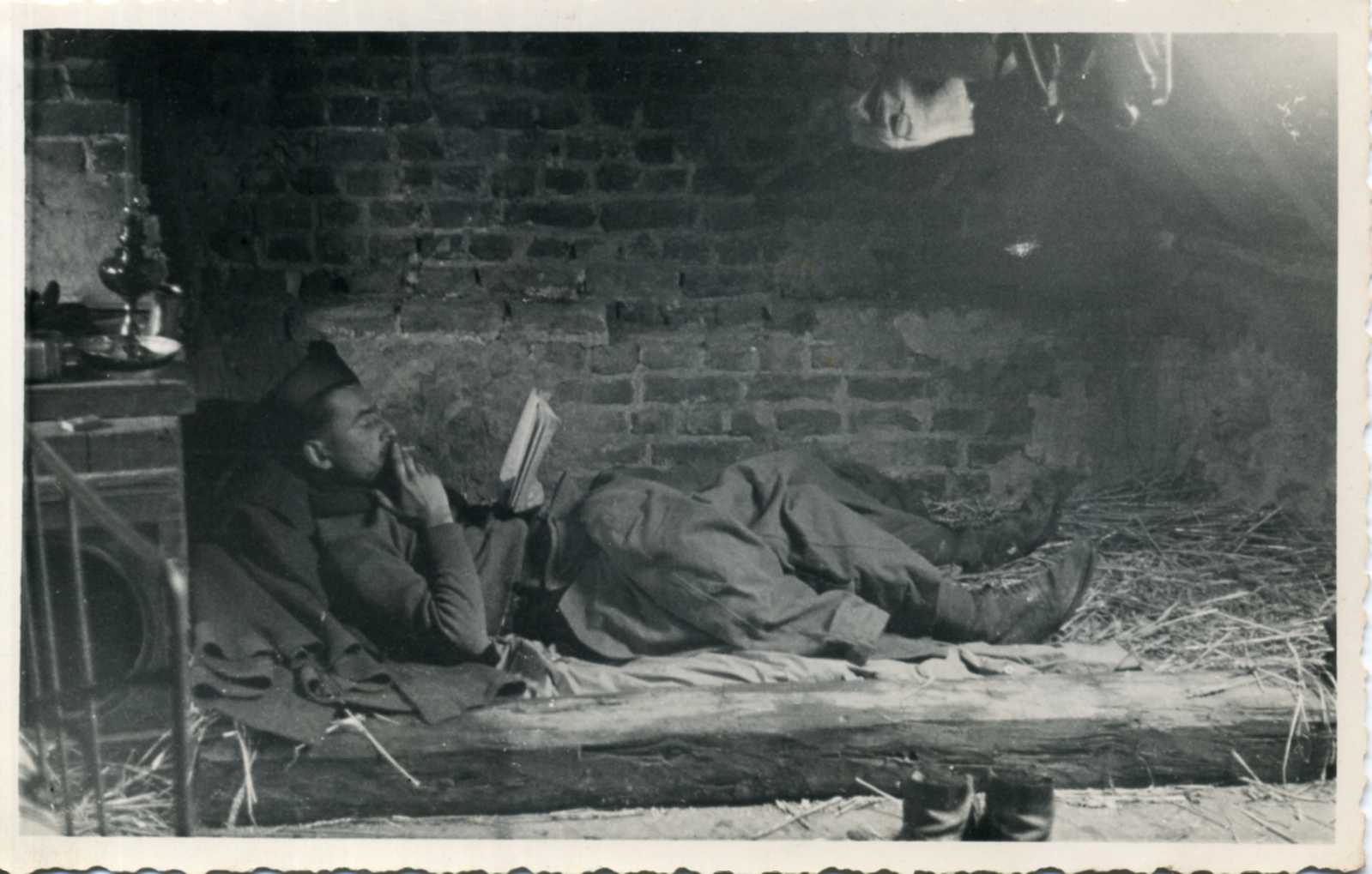

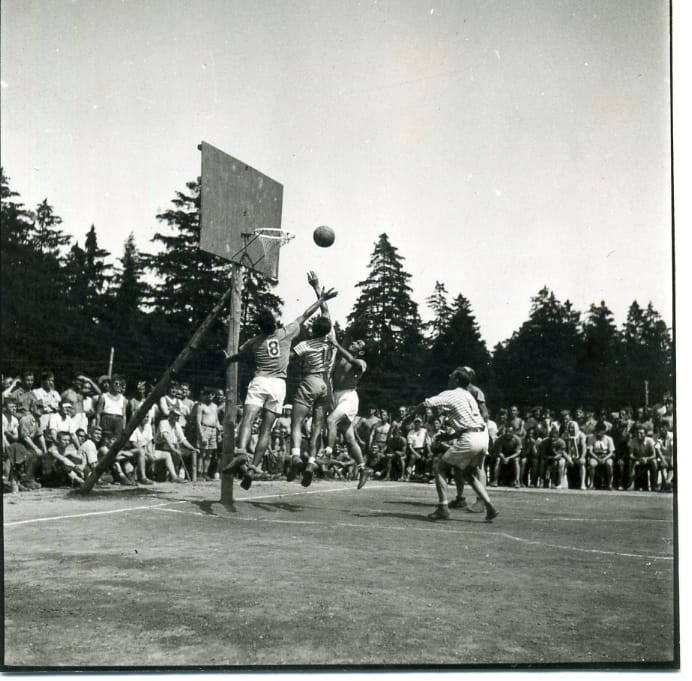

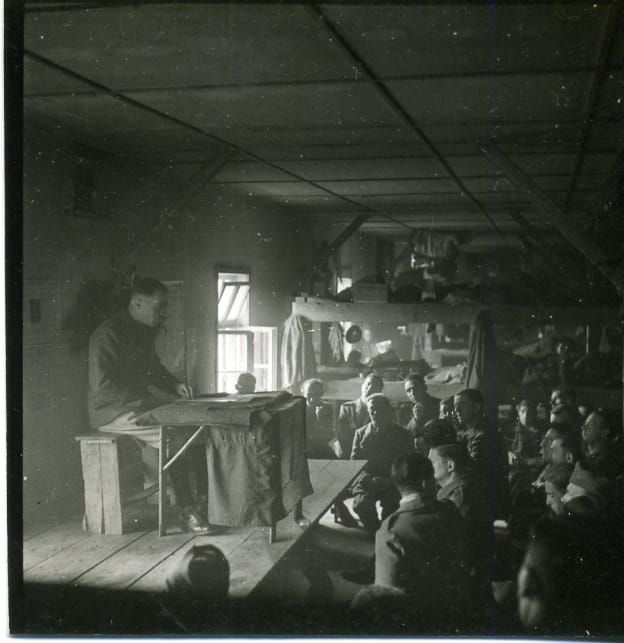

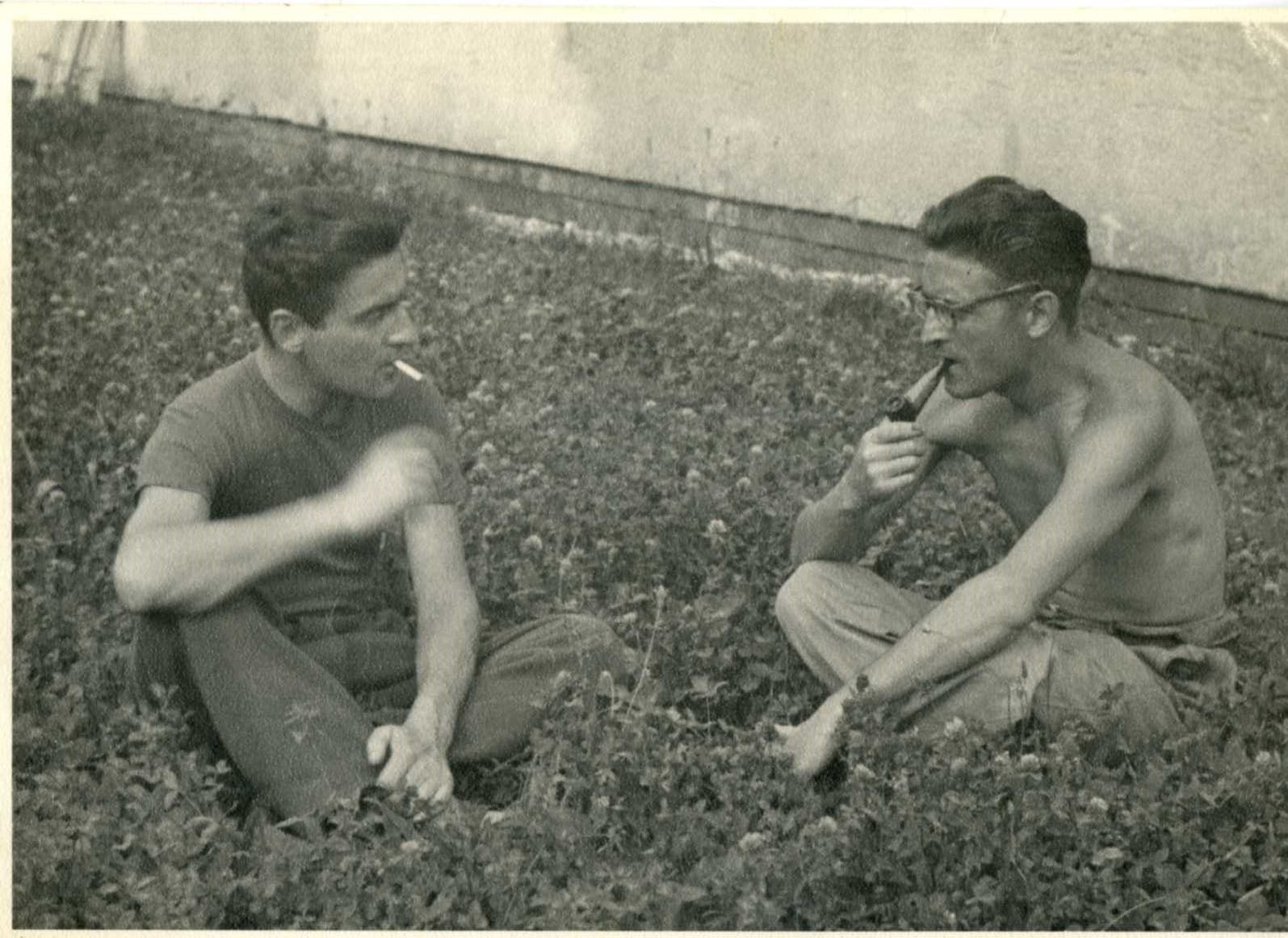

Life at Stalag VII-A between 1940 and 1942. All photos at www.isabelleroughol.com/stalag-7a/. Photo credit: Pierre Roughol archives. (No reuse without permission.)

A photojournalist, Pierre was allowed to keep his camera and document life inside Stalag VII-A. Censors checked every frame though, which can sometimes make the POW camp look like a boyscout retreat. Starvation is only hinted at in the thinness of arms, boredom in the dullness of eyes. Nonetheless, Pierre's pictures are a rare account of the life of the 1.6 million Frenchmen held captive in Germany from 1940 and the many others who joined them later from the Western and Eastern fronts. Conditions only got worse as the war progressed and the camp became overcrowded and undersupplied. (Pierre's photos are now all digitised and preserved here, and the never-ending work of research and interpretation, which my brother François and I undertook a decade ago, continues.) Gilbert, for his part, left us handwritten notebooks from his captivity. I am only beginning to transcribe them.

Pierre rushed back to Stalag VII-A in early May 1945 and must have been on the road in Bavaria when the VE Day bells rang. He arrived in Moosburg to find the camp ablaze. He told the story in his own words to French magazine Radar on 13 March 1949 (translation below).

"If Radar had asked me for “the picture I’m proudest of,” I wouldn’t have known what to say. Personally, I don’t think you can be proud of a photograph. In the field, a good photo is a gift from God. The only skill is in taking advantage of the few seconds when providence offers it up. Or it’s a planned picture, made to order, and I would almost say staged. You might as well work in cinema.

Choosing my most moving picture is easier. I picked this prisoner limping out of Stalag VII-A, where I spent three years myself, because it was a picture I wanted to take for five years.

On May 5, 1945, as a war correspondent embedded with the 1st French Army, I learned on the radio that the Americans, after taking Munich, had just freed a prisoner camp near Moosburg. I immediately decided to apply for a mission order and jumped into my car to pick up my friends. It took me three days to leave and two to travel from Lindau to Moosburg, across a freshly defeated Germany. Here was that once triumphant country, which used us as forced laborers. Here were those sad landscapes we only saw framed by barbed wire. I was going to drive through the main gate, barrel down the central path, find my friends and keep my promise to come back and take them home.

At first I struggled to get inside the camp. There were no more German officers, but an American provost marshal barred my entry. I found out that barbed wire works both ways. Eventually I learned that French prisoners had been evacuated the day before. Finally I walked in, with a heavy heart. This was where I used to live ! We got used to all that filth, we built something of a social life. I couldn't believe it! The camp was almost empty. American soldiers went through the barracks, piled up the straw beds, boxes, letters, old clothes. Then they doused it all with gasoline and set it on fire.

I went back up the main path to leave. Still I wanted to take one final image of my old life. The first barracks were still occupied by Yugoslavs, Greeks, Poles. Crossing the camp’s first enclosure, I passed a Serbian prisoner leaving on his crutches. At the same time I heard an explosion. The Americans had just set fire to the other end of the camp. Barrack 40 was burning, the one for convicts. I could feel my shot, I jumped out of the car, I laid flat on the pavement. That was it, the picture was taken.

I returned to the 1st Army, picking up along the way a few French prisoners who’d been left back in farm Kommandos. Back at the press camp, I sent “the photo” to my newspaper.

It was never published... POWs had fallen out of fashion.

This moment in our lives was finished, gone, the prisoner off on his crutches and Stalag VII-A up in smoke."

Hey, you read to the end!

Don’t miss future articles like this one; let me into your inbox.